Rudolph Rummel

Talks About the Miracle

of Liberty and Peace*

Since the late nineteenth century, most intellectuals have embraced the illusion that government could somehow be tamed. They promoted a vast expansion of government power supposedly to do good. But the twentieth century turned out to be the bloodiest in human history, confirming the worst fears of classical liberals who had always warned about government power. Perhaps nobody has done a better job documenting its horrors than University of Hawaii political science professor emeritus Rudolph J. Rummel. Little known outside the academic community, he suddenly received much attention when he wrote Death by Government (Transaction, 1994). In the book, Rummel analyzed 8,193 estimates of government killings and reported that throughout history governments have killed more than 300 million people--with more than half, or 170 million, killed during the twentieth century. These numbers don't include war deaths!

Other Democratic Peace Documents On This Site Nontechnical: What is the "democratic peace"?

"Waging denuclearization and social justice through democracy"

"The rule of law: towards eliminating war"

"Freedom of the press--A Way to Global Peace"

"Convocation Speech"

City Times Interview

Professional: Bibliography on Democracy and War

Q & A On Democracies Not Making War on Each Other

But What About...?

"The democratic peace: a new idea?"

Statistical: "Libertarianism and International Violence"

"Libertarianism, Violence Within States, and the Polarity Principle"

"Libertarian Propositions on Violence Within and Between Nations: A Test Against Published Research Results"

"Democracies ARE less warlike than other regimes"

Books: Vol. 2: The Conflict Helix (see Chapter 35)

Vol. 4: War, Power, Peace (see e.g., Propositions 16.11 and 16.27

Statistics of Democide

The Miracle That Is Freedom

Power Kills Rummel went on to identify keys for peace, noting which kinds of governments engaged in wars during the past 200 years. In his latest books, Power Kills (Transaction, 1997) and The Miracle That Is Freedom (Martin Institute, University of Idaho, 1997), he reported his finding that liberal democracies are far less warlike than authoritarian or totalitarian regimes. Indeed, he could not find a single case of a war between two liberal democracies. He presented compelling evidence that the most effective way to secure peace is to secure liberty by limiting government power. Last year he was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize. To be sure, classical liberals always knew that liberty and peace go together. Classical liberalism blossomed after centuries of brutal war. Mindful of how casually kings had launched so many senseless wars, America's Founders gave the war-making power to Congress, not to the chief executive. Peace was a primary passion of Richard Cobden and John Bright as they launched the successful movement for free trade. By giving people on both sides of a border easy access to resources, they believed free trade would eliminate major provocations for war and strengthen the self-interest of nations to get along. The international movement for liberty was a peace movement. But during the late nineteenth century, statists relentlessly attacked classical liberalism, promoted a vast expansion of government power and imperialism and blamed escalating conflicts on capitalism. The dynamic link between liberty and peace was forgotten. Rummel's personal experience led him to explore these great themes. Born in Cleveland, he endured parents who never seemed to get along. This experience, he says, "made me hate conflict--the bickering, the emotion, the yelling, the irrationality." He joined the army during the Korean War as a way of escaping the slums. He was stationed in Japan, he saw firsthand the horrifying destruction of war, and he found the Japanese friendly. It led him to ask why we had made war on each other and to study war later when he went to college. Meanwhile, he recalls, "I became thoroughly captured by science fiction. It occupied my free time, being to me what rock, movies, and television are to contemporary youth. I got my hands on whatever science fiction pulp magazines or books I could find to read; and unbeknownst to me at the time, not only got something of an education in basic science, but also developed scientific norms. I simply fell in love with science and took it as axiomatic that truth came from science, and that to be a scientist one had to learn mathematics." After the Korean War, Rummel enrolled at Ohio State University--even though he hadn't been to high school. A year later he transferred to the University of Hawaii because he had become fascinated with Asian culture. "There I discovered that I could actually, as a student and later as a professor, study war. I was elated. From that time on, I never had any doubt this was what I must do."

He earned his master's degree at Hawaii, then went to Northwestern University. After teaching stints at Indiana University and Yale University, he returned to Hawaii, where he has been ever since.

During the 1960s, he wrote articles for Peace Research Society Papers, Journal of Conflict Resolution, American Political Science Review, World Politics, Orbis, and other journals, and he contributed chapters to many edited books. He wrote the five-volume Understanding Conflict and War (1975, 1976, 1977, 1979, 1981). Then came In the Minds of Men: Principles Toward Understanding and Waging Peace (1984), Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murders 1917-1987 (1990), The Conflict Helix: Principles and Practices of Interpersonal, Social, and International Conflict and Cooperation (1991), China's Bloody Century: Genocide and Mass Murder since 1900 (1991), and Democide: Nazi Genocide and Mass Murder (1992).

Despite his voluminous writings, Rummel's findings were ignored because, among other things, they posed an unacceptable challenge to statist dogmas that dominated the intellectual world. But after the collapse of so many communist regimes, he could no longer be denied.

Now retired from teaching, Rummel works mostly at his Kaneohe, Hawaii, home, which is filled with books and Asian art. Recently we talked with him about war, peace, and liberty, issues which thinkers have grappled with for thousands of years.

The Freeman: Could you tell us what your research has revealed about government power? Rummel: Concentrated political power is the most dangerous thing on earth.

During this century's wars, there were some 38 million battle deaths, but almost four times more people--at least 170 million--were killed by governments for ethnic, racial, tribal, religious, or political reasons. I call this phenomenon democide, and it means that authoritarian and totalitarian governments are more deadly than war.

Many people are aware that some 60 million people died during World War II. What's much less well known is that only about 16 million of the World War II deaths involved combatants. [Most of the remaining dead were killed in cold blood by one government or another. The Soviet Union alone murdered about 10 million of its citizens during the war.]

When you have a very powerful dictatorship, it doesn't follow automatically that a country will be violent. But I find the most violent countries are authoritarian or totalitarian. Lord Acton insisted government officials be judged by the same moral standards you apply to ordinary people, and I do that, often to the discomfort of my political science colleagues. For instance, at one conference where I delivered a paper, I could see people wince when I referred to the late North Korean dictator Kim Il-sung as a murderer. He [probably] was responsible for about 1.7 million deaths. A lot of us can talk about an individual killer as a murderer--somebody like "Jack the Ripper," who killed about a half-dozen people--but in polite society you don't usually hear a famous "statesman" described as a murderer.

The Freeman: Who were the biggest murderers of the twentieth century? Rummel: Soviet Communists top the list, having killed almost 62 million of their own people and foreign subjects. I figure Stalin was responsible for nearly 43 million deaths. Most of them, about 33 million, were the consequence of lethal forced labor in the gulag.

Chinese Communists were next, murdering about 35 million of their people. More than a million died during Chairman Mao's "Cultural Revolution" alone. In addition to all these killed, 27 million died from the famine resulting from Chairman Mao's insane economic policies.

Percentage-wise, communist Cambodia was the worst. Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge murdered about 2 million people, almost a third of the population, between 1975 and 1979. They murdered Muslim Chains, Cambodian, Vietnamese, Buddhist Monks, military officers, anybody who was fluent in a foreign language, anybody who had a college education or professional training, and certainly anybody who violated their regulations. The odds of an average Cambodian surviving Pol Pot's regime were about 2 to 1.

Millions more people were murdered by communist regimes in Afghanistan, Albania, Bulgaria, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Ethiopia, East Germany, Hungary, Laos, Mongolia, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Poland, Romania, Vietnam, and Yugoslavia. All told, I estimate communist regimes murdered more than 110 million people.

Another 30 million people died during wars and rebellions provoked by communist regimes.

There were plenty of other murderous twentieth-century regimes, too. Between 1900 and 1920, Mexico murdered about a million poor Indians and peasants. After World War II, the Polish government expelled ethnic Germans, murdering about a million. Pakistan murdered about a million Bengalis and Hindus in 1971, Japanese militarists murdered about 6 million Chinese, Indonesians, Koreans, Filipinos, and others during World War II. Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist Chinese murdered nearly 10 million people between 1928 and 1949.

Although most people have heard that Hitler murdered almost 6 million Jews, few people seem to be aware that Hitler murdered a total of 20 million people--including gypsies, homosexuals, Dutchmen, Italians, Frenchmen, Balts, Slavs, Czechs, Poles, Ukrainians, and others.

The Freeman: Your research ought to give one renewed appreciation for the greater peace of the nineteenth century, the heyday of classical liberalism. Rummel: Yes. During earlier eras, whenever power has been unlimited, savagery was horrifying.

Ancient histories abound with accounts of cities being sacked and all inhabitants slaughtered. In 1099 A.D., Christian Crusaders seized Jerusalem and massacred between 40,000 and 70,000 men, women, and children. During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the Sultan of Delhi reportedly murdered hundreds of thousands of his subjects. The Turkic conqueror Tamerlane slaughtered some 100,000 people near Delhi.

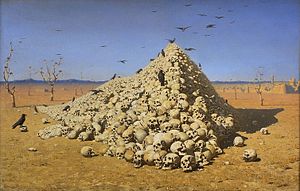

Mongols were the most monstrous murderers before the modern era. In 1221, a Mongol army captured Merv and slaughtered some 1.3 million inhabitants. That same year, the Mongol Tului slaughtered as many as 1.3 million more in Meru Chahjan. Soon afterward, Jinghiz Khan slaughtered about 1.6 million around Herat. To acquire and maintain his political power, Khubilai Khan reportedly slaughtered as many as 18 million people. I estimate Mongols slaughtered [in total] about 30 million Arabs, Chinese, Persians, Russians, and others.

China has been bathed in blood. During the eight years (221-207 B.C.) that the Qin dynasty struggled for supremacy, the estimated population of China dropped from 20 million to 10 million. In the Three Kingdom period (222-589 A.D.) the population dropped from something like 50 million to about 7 million. After the Ming emperor Chang Hsien-chung conquered Szechwan province, he ordered scholars, merchants, officials, wives, and concubines murdered. He had their feet cut off and gathered into huge piles. In 1681, following the Triad Rebellion, an estimated 700,000 people were executed in one province alone. The great peace of the nineteenth century didn't touch China where, during the 15-year Teiping Rebellion, perhaps 600 cities were reportedly ruined, and as many as 40 million people were killed. Moslem rebellions in Yunnan province resulted in some 5 million deaths.

There were atrocities in Western Europe. Jews were blamed for the Black Death of 1347-1352, and thousands were slaughtered. The Spanish Inquisition killed between 100,000 and 200,000 people who were branded "heretics." Fanatical Protestants killed perhaps 100,000 women as "witches" during the Reformation. On August 24, 1572--St. Bartholomew's Day--the French King Charles IX or his officials ordered assaults on French Calvinists, and an estimated 35,000 were killed. During the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), perhaps 7.5 million people were killed. An estimated 137,000 people were murdered during the French Revolution and the ensuing civil war.

And, yes, there were horrors in the Americas. Aztecs killed people as part of their religious rituals, and Spanish conquistadors claimed to have counted 136,000 skulls outside Tenochtitlan. The Incas killed thousands for their religion, too. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, an estimated 1.5 million slaves died while they were being transported across the Atlantic. Between 10,000 and 25,000 North American Indians were killed as the United States expanded westward.

These are just some of the worst horrors. Before the twentieth century, I estimate that governments were responsible for at least 89 million deaths and possibly as many as 260 million. My best guess is around 133 million.

Again, these numbers don't count battle deaths. I estimate that before the twentieth century, those amounted to some 40 million.

I want to caution readers about the misleading precision of these numbers. They represent the totals [consolidation] of many estimates. I analyzed the estimates as best I could. Obviously, the farther back one goes in history, it's harder to verify numbers. Which is why I tried to establish a range and then indicate a magnitude which seems best supported by evidence. Although the numbers shouldn't be taken literally, I believe they do help identify the worst murderers and the circumstances.

I conclude that nobody can be trusted with unlimited power. The more power a regime has, the more likely people will be killed. This is a major reason for promoting freedom.

The Freeman: What were the biggest surprises to emerge from your research? Rummel: First of all, the unprecedented magnitude of mass murder. Nobody had tried to estimate it before. We have many books about demographics, like total population, the number of people who own telephones and cars. There's data on the number of people who die from heart attacks, strokes, cancer, and accidents. But until recently, there hasn't been any reliable information on the number of people killed by governments. Even though many of us were aware that governments were major killers, the numbers still come as a shock.

During the twentieth century, 14 regimes murdered over a million people [each], and it would be hard to find a scholar who could name half these regimes.

I was shocked to find that governments kill people to fill a quota. For instance, in the Soviet Union under Stalin and China under Mao, the government would set execution quotas. They would decree that perhaps 5 percent of the people are counterrevolutionaries, so kill 5 percent of the people. Writers, entrepreneurs, you name it--kill 5 percent. In retrospect, I can see that murder by quota was the natural thing for these regimes to do, because they had central planners direct production of iron, steel, wheat, pigs, and almost everything else by quota.

I was shocked to discover how officials at the highest levels of government planned mass murder. The killing they would delegate to humble cadres. So much for the notion of government benevolence. Powerful governments can be like gangs, stealing, raping, torturing, and killing on a whim.

Another shocking thing, for me as a political scientist, was to see how political scientists almost everywhere have promoted the expansion of government power. They have functioned as the clergy of oppression.

The Freeman: What was difficult about estimating the magnitude of government killing? Rummel: There's a vast literature, but it's widely scattered, it comes in many different forms, and it isn't indexed or otherwise organized. There are only a few scholarly books, such as Robert Conquest's work on Stalin's Great Terror, estimating the number of people murdered by government. It took me about eight years to go through all the relevant books, reports, articles, chapters, clippings, and the like and sort the information I found.

I then determined the lowest estimates and the highest estimates of democide, and arrived at what I call a "prudent" figure depending on various factors. I concluded that during the twentieth century governments killed at least 80 million people and possibly as many as 300 million, but the most likely number is about 170 million.

Even if it turned out that the low estimates were correct, it's more than twice as many people as have been killed in all the wars before the twentieth century.

From a moral standpoint, I doubt it matters much whether the number is 80 million or 170 million or 300 million. It's an unprecedented human and moral catastrophe.

The Freeman: Since authoritarian and totalitarian regimes suppress their records, how did you develop estimates for their murders? Rummel: Well, among the principal sources, there are usually those sympathetic to a regime and those hostile to it.

The low estimate for twentieth-century mass murders, 80 million, comes mainly from sources sympathetic to the regimes carrying out the murders!

In a few cases, regimes have publicized their murders, often to intimidate people. For instance, Communist Chinese government newspapers would report speeches by officials in which one might boast, "We killed 2 million bandits in the 10th region between November and January." The term "bandit" was standard lingo for presumed "counterrevolutionaries."

After Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1979, the Vietnamese justified the invasion by releasing data about Cambodian mass murders. They let Westerners see evidence of Khmer Rouge horrors.

Many people who escaped totalitarian regimes brought data about mass murders. They were unsympathetic sources, of course. For instance, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's volumes documenting the murderous Soviet gulag. I might add that he had an enormous impact undermining the moral claims of socialism. Many intellectuals, especially in Europe, remained socialists, but they turned against Soviet communism--and the Soviet Union, remember, was long touted as the place where socialism had achieved industrial power and social justice.

The Freeman: Tell us about your findings on peace. Rummel: First, long [well]-established democracies don't wage war on each other, and they rarely commit other kinds of violence against each other, either.

Second, the more democratic two countries are, the less likely they will go to war against [have intense violence with] each other.

Third, the more democratic a country is, the lower the level of violence when there's a conflict with another country.

Fourth, the more democratic a country, the less likely it will have domestic political violence.

Fifth, the bottom line: democratic freedom is a method of nonviolence.

The Freeman: What do you mean by "democratic"? Rummel: People have equal rights before the law. Fundamental civil liberties like freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, freedom of association. Free markets. Constitutional limitations on government power. Policies and leaders are determined through open, competitive elections where at least two-thirds of adult males have the franchise. Countries like the United States, Canada, Denmark, France, Great Britain, Sweden, and Switzerland.

The Freeman: Tell us about your evidence that freedom promotes peace. Rummel: I reviewed the evidence and historical studies going back to the classical Greeks.

For example, if one counts as a war any conflict in which 1,000 or more people were killed since 1816, the end of the Napoleonic wars, then there were . . . [no wars] between two democracies. There were 155 pairs [such as the Great Britain versus Germany, the U.S. versus Japan].involving a democracy versus a non-democracy and 198 pairings of two non-democracies [such as Japan versus China, Germany versus the U.S.S.R.].

The period between 1946 and 1986 involved the largest number of democracies--the toughest test for the link between democracy and peace. During this period, 45 countries qualified as democracies, and 109 as non-democracies. Consequently, these countries could be paired 6,876 ways, of which 990 were democracy-democracy combinations. Without going into detail, I applied the binomial theorem to show that the odds were 100 to 1 against the absence of war occurring by chance.

When you analyze other periods, qualify countries with various definitions of democracy, and estimate the impact of other factors such as geographic distance, economic development, military alliances, trade, and so on, democracy always comes out as the best explanation for the absence of war.

This is an incredible finding. It's like discovering a cure for cancer. We have a solution for war. It is to expand the sphere of liberty.

The Freeman: Why do you think liberal democracies tend to be peaceful? Rummel: Power is dispersed through many different families, churches, schools, universities, corporations, partnerships, business associations, scientific societies, unions, clubs, and myriad other associations. There's plenty of competition, and people have overlapping interests. The social order isn't controlled by anybody--it evolves spontaneously.

Democracy is a culture of political compromise, free exchange, peaceful negotiation, toleration of differences. Because time is needed for a democratic culture to develop and gain widespread acceptance, I stress that a peace dividend is achieved as a democracy becomes well-established.

Even though there might be a lot of government interference in daily life through minimum-wage laws, environmental laws, drug prohibition, government schools, and other policies, as long as a democratic culture remains strong, government officials must still negotiate with each other as well as with private interests.

By contrast, as Hayek explained in The Road to Serfdom--in his famous chapter "Why the worst get on top"--centralized government power attracts aggressive, domineering personalities. They are the most likely to gain power. And the more power they have, naturally the less subject they are to restraint. The greater the likelihood such a country will pursue aggressive policies. The highest risks of war occur when two dictators face each other. There's likely to be a struggle for supremacy.

Another important reason why democracies tend to be peaceful is that people have a say in whether their government goes to war. They don't want to die, they don't want to see their children become casualties, they don't want the higher taxes, regimentation, inflation, and everything else that comes with war.

When democracies do enter a war for reasons other than self-defense, politicians often find it necessary to deceive the public. In 1916, this was the case when Woodrow Wilson campaigned on a promise to keep the United States out of World War I, then maneuvered the country into it. And again in 1940, Franklin Roosevelt campaigned on a promise to keep out of World War II, then conducted foreign policy not as a neutral but as an ally of Great Britain and an enemy of Germany. My point is that in the United States, a liberal democracy, there was considerable popular opposition to entering foreign wars, and both presidents deceived the public, which wanted to remain at peace.

The Freeman: Some people suggest there are big exceptions to your claim that democracies don't make war against each other, like the War of 1812 and the American Civil War. Rummel: The War of 1812, of course, was between the United States and Great Britain, but the franchise in Great Britain was then severely limited. Parliament was dominated by members from "rotten boroughs," districts that aristocrats controlled. Booming regions like Manchester had little, if any, representation. Serious electoral reforms didn't begin to come until 1832, and major extensions of the franchise came decades later.

As for the Civil War, I don't consider the South a sovereign democracy. Only about 35 percent or 40 percent of the electorate--free males--had the franchise. President Jefferson Davis was appointed by representatives of the Confederate states, not elected. There was an election in 1861, but he didn't face any opposition....

There are other possible exceptions people sometimes mention, but none of them involve established democracies.

The Freeman: If democracies tend not to wage war against each other, they sometimes promote coups, assassinations, and other forms of violence abroad. Rummel: Such violence tends to be the work of covert agencies like the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, which have considerable discretionary power and aren't subject to detailed scrutiny by democratically elected representatives.

The Freeman: What about Western colonialism, which involved violence? Rummel: Democracies committed less violence than other types of governments.

For example, compare the way the United States and Britain treated their colonial subjects with what Imperial Germany did. In Africa, the Germans conducted a murderous campaign against the Hereros tribe, and some 65,000 people were murdered. Far worse was the Soviet Union which murdered millions of people in territories it conquered.

Democracies have given up their colonies with less violence than authoritarian or totalitarian regimes. Recall how the British gave independence to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. The most tragic fighting was between local rivals such as Moslems and Hindus. Hawaii, which the United States acquired by force, voted overwhelmingly to become a state, and Puerto Rico voted to remain a U.S. territory.

It's true some democracies did worse. France waged long wars in Indochina and Algeria. But the exceptional situation for democracies is the norm for authoritarian and totalitarian regimes like militarist Japan, fascist Italy, the Soviet Union, and Communist China.

The Freeman: Some people might say that although the United States is a liberal democracy, there's plenty of domestic violence. Rummel: It's true the United States has the highest murder rate among Western democracies, but there's decidedly more violence in other countries like Brazil, Burundi, Colombia, India, Peru, Rwanda, Sri Lanka, and Uganda. The United States is well below the world average in domestic violence.

More to the point, I'm talking about how to minimize political violence. While it certainly isn't the only source of violence, it's the worst. I say that securing liberty is the only reliable way of minimizing political violence--revolution, assassination, civil war, military coups, guerrilla war, violent antigovernment riots, and so on.

The Freeman: Did your research influence your personal views? Rummel: It helped convert me from socialist to libertarian.

If somebody had given a speech three decades ago, saying freedom is what promotes peace, and tyranny promotes violence, I would have said that was a simplistic explanation which couldn't possibly hold up. Much of my career, I had believed that complex social behavior requires many variables to explain and a complex theory. The surprise was that when I did the research, freedom came out as the single most important factor for peace and nonviolence. That freedom so preserves and secures life I now call the miracle of freedom.

The Freeman: What's your outlook for liberty and peace? Rummel: Our challenge is to extend the sphere of liberty which, in turn, will extend the sphere of peace.

There has been some heartening progress in recent decades. For instance, while there are many disputes in Western Europe, where democracy is securely established, they're routinely handled through diplomatic channels, the European Community, or other peaceful means. France and Germany even have been considering a common army. This would have been inconceivable to people during the 1930s.

Closer to home, there's the border between the United States and Canada. It's one of the world's longest borders, and it's unarmed. People in North America take it for granted, but it's quite an amazing phenomenon when you consider all the wars still being fought over territory. These examples involve liberal democracies, and peace is the norm.

Markets are strong influences for democracy. For instance, foreign direct investment, which now exceeds $1.5 trillion, transfers technology to host countries. It provides jobs. It trains local people in business. It helps nations develop their resources and human capital. Most important, foreign direct investment promotes economic development and a civil society independent of government, and this promotes democracy. America should cut its own trade barriers and encourage freer trade everywhere.

America should apply nonviolent pressure aimed at persuading nondemocratic elites to improve the human rights of their people and gradually move toward democracy. I envision a nonviolent crusade by the democracies, the most important one since the great crusade against slavery.

The Freeman: Thank you very much.

Talks About the Miracle

of Liberty and Peace*

Since the late nineteenth century, most intellectuals have embraced the illusion that government could somehow be tamed. They promoted a vast expansion of government power supposedly to do good. But the twentieth century turned out to be the bloodiest in human history, confirming the worst fears of classical liberals who had always warned about government power. Perhaps nobody has done a better job documenting its horrors than University of Hawaii political science professor emeritus Rudolph J. Rummel. Little known outside the academic community, he suddenly received much attention when he wrote Death by Government (Transaction, 1994). In the book, Rummel analyzed 8,193 estimates of government killings and reported that throughout history governments have killed more than 300 million people--with more than half, or 170 million, killed during the twentieth century. These numbers don't include war deaths!

Other Democratic Peace Documents On This Site Nontechnical: What is the "democratic peace"?

"Waging denuclearization and social justice through democracy"

"The rule of law: towards eliminating war"

"Freedom of the press--A Way to Global Peace"

"Convocation Speech"

City Times Interview

Professional: Bibliography on Democracy and War

Q & A On Democracies Not Making War on Each Other

But What About...?

"The democratic peace: a new idea?"

Statistical: "Libertarianism and International Violence"

"Libertarianism, Violence Within States, and the Polarity Principle"

"Libertarian Propositions on Violence Within and Between Nations: A Test Against Published Research Results"

"Democracies ARE less warlike than other regimes"

Books: Vol. 2: The Conflict Helix (see Chapter 35)

Vol. 4: War, Power, Peace (see e.g., Propositions 16.11 and 16.27

Statistics of Democide

The Miracle That Is Freedom

Power Kills Rummel went on to identify keys for peace, noting which kinds of governments engaged in wars during the past 200 years. In his latest books, Power Kills (Transaction, 1997) and The Miracle That Is Freedom (Martin Institute, University of Idaho, 1997), he reported his finding that liberal democracies are far less warlike than authoritarian or totalitarian regimes. Indeed, he could not find a single case of a war between two liberal democracies. He presented compelling evidence that the most effective way to secure peace is to secure liberty by limiting government power. Last year he was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize. To be sure, classical liberals always knew that liberty and peace go together. Classical liberalism blossomed after centuries of brutal war. Mindful of how casually kings had launched so many senseless wars, America's Founders gave the war-making power to Congress, not to the chief executive. Peace was a primary passion of Richard Cobden and John Bright as they launched the successful movement for free trade. By giving people on both sides of a border easy access to resources, they believed free trade would eliminate major provocations for war and strengthen the self-interest of nations to get along. The international movement for liberty was a peace movement. But during the late nineteenth century, statists relentlessly attacked classical liberalism, promoted a vast expansion of government power and imperialism and blamed escalating conflicts on capitalism. The dynamic link between liberty and peace was forgotten. Rummel's personal experience led him to explore these great themes. Born in Cleveland, he endured parents who never seemed to get along. This experience, he says, "made me hate conflict--the bickering, the emotion, the yelling, the irrationality." He joined the army during the Korean War as a way of escaping the slums. He was stationed in Japan, he saw firsthand the horrifying destruction of war, and he found the Japanese friendly. It led him to ask why we had made war on each other and to study war later when he went to college. Meanwhile, he recalls, "I became thoroughly captured by science fiction. It occupied my free time, being to me what rock, movies, and television are to contemporary youth. I got my hands on whatever science fiction pulp magazines or books I could find to read; and unbeknownst to me at the time, not only got something of an education in basic science, but also developed scientific norms. I simply fell in love with science and took it as axiomatic that truth came from science, and that to be a scientist one had to learn mathematics." After the Korean War, Rummel enrolled at Ohio State University--even though he hadn't been to high school. A year later he transferred to the University of Hawaii because he had become fascinated with Asian culture. "There I discovered that I could actually, as a student and later as a professor, study war. I was elated. From that time on, I never had any doubt this was what I must do."

He earned his master's degree at Hawaii, then went to Northwestern University. After teaching stints at Indiana University and Yale University, he returned to Hawaii, where he has been ever since.

During the 1960s, he wrote articles for Peace Research Society Papers, Journal of Conflict Resolution, American Political Science Review, World Politics, Orbis, and other journals, and he contributed chapters to many edited books. He wrote the five-volume Understanding Conflict and War (1975, 1976, 1977, 1979, 1981). Then came In the Minds of Men: Principles Toward Understanding and Waging Peace (1984), Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murders 1917-1987 (1990), The Conflict Helix: Principles and Practices of Interpersonal, Social, and International Conflict and Cooperation (1991), China's Bloody Century: Genocide and Mass Murder since 1900 (1991), and Democide: Nazi Genocide and Mass Murder (1992).

Despite his voluminous writings, Rummel's findings were ignored because, among other things, they posed an unacceptable challenge to statist dogmas that dominated the intellectual world. But after the collapse of so many communist regimes, he could no longer be denied.

Now retired from teaching, Rummel works mostly at his Kaneohe, Hawaii, home, which is filled with books and Asian art. Recently we talked with him about war, peace, and liberty, issues which thinkers have grappled with for thousands of years.

The Freeman: Could you tell us what your research has revealed about government power? Rummel: Concentrated political power is the most dangerous thing on earth.

During this century's wars, there were some 38 million battle deaths, but almost four times more people--at least 170 million--were killed by governments for ethnic, racial, tribal, religious, or political reasons. I call this phenomenon democide, and it means that authoritarian and totalitarian governments are more deadly than war.

Many people are aware that some 60 million people died during World War II. What's much less well known is that only about 16 million of the World War II deaths involved combatants. [Most of the remaining dead were killed in cold blood by one government or another. The Soviet Union alone murdered about 10 million of its citizens during the war.]

When you have a very powerful dictatorship, it doesn't follow automatically that a country will be violent. But I find the most violent countries are authoritarian or totalitarian. Lord Acton insisted government officials be judged by the same moral standards you apply to ordinary people, and I do that, often to the discomfort of my political science colleagues. For instance, at one conference where I delivered a paper, I could see people wince when I referred to the late North Korean dictator Kim Il-sung as a murderer. He [probably] was responsible for about 1.7 million deaths. A lot of us can talk about an individual killer as a murderer--somebody like "Jack the Ripper," who killed about a half-dozen people--but in polite society you don't usually hear a famous "statesman" described as a murderer.

The Freeman: Who were the biggest murderers of the twentieth century? Rummel: Soviet Communists top the list, having killed almost 62 million of their own people and foreign subjects. I figure Stalin was responsible for nearly 43 million deaths. Most of them, about 33 million, were the consequence of lethal forced labor in the gulag.

Chinese Communists were next, murdering about 35 million of their people. More than a million died during Chairman Mao's "Cultural Revolution" alone. In addition to all these killed, 27 million died from the famine resulting from Chairman Mao's insane economic policies.

Percentage-wise, communist Cambodia was the worst. Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge murdered about 2 million people, almost a third of the population, between 1975 and 1979. They murdered Muslim Chains, Cambodian, Vietnamese, Buddhist Monks, military officers, anybody who was fluent in a foreign language, anybody who had a college education or professional training, and certainly anybody who violated their regulations. The odds of an average Cambodian surviving Pol Pot's regime were about 2 to 1.

Millions more people were murdered by communist regimes in Afghanistan, Albania, Bulgaria, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Ethiopia, East Germany, Hungary, Laos, Mongolia, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Poland, Romania, Vietnam, and Yugoslavia. All told, I estimate communist regimes murdered more than 110 million people.

Another 30 million people died during wars and rebellions provoked by communist regimes.

There were plenty of other murderous twentieth-century regimes, too. Between 1900 and 1920, Mexico murdered about a million poor Indians and peasants. After World War II, the Polish government expelled ethnic Germans, murdering about a million. Pakistan murdered about a million Bengalis and Hindus in 1971, Japanese militarists murdered about 6 million Chinese, Indonesians, Koreans, Filipinos, and others during World War II. Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist Chinese murdered nearly 10 million people between 1928 and 1949.

Although most people have heard that Hitler murdered almost 6 million Jews, few people seem to be aware that Hitler murdered a total of 20 million people--including gypsies, homosexuals, Dutchmen, Italians, Frenchmen, Balts, Slavs, Czechs, Poles, Ukrainians, and others.

The Freeman: Your research ought to give one renewed appreciation for the greater peace of the nineteenth century, the heyday of classical liberalism. Rummel: Yes. During earlier eras, whenever power has been unlimited, savagery was horrifying.

Ancient histories abound with accounts of cities being sacked and all inhabitants slaughtered. In 1099 A.D., Christian Crusaders seized Jerusalem and massacred between 40,000 and 70,000 men, women, and children. During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the Sultan of Delhi reportedly murdered hundreds of thousands of his subjects. The Turkic conqueror Tamerlane slaughtered some 100,000 people near Delhi.

Mongols were the most monstrous murderers before the modern era. In 1221, a Mongol army captured Merv and slaughtered some 1.3 million inhabitants. That same year, the Mongol Tului slaughtered as many as 1.3 million more in Meru Chahjan. Soon afterward, Jinghiz Khan slaughtered about 1.6 million around Herat. To acquire and maintain his political power, Khubilai Khan reportedly slaughtered as many as 18 million people. I estimate Mongols slaughtered [in total] about 30 million Arabs, Chinese, Persians, Russians, and others.

China has been bathed in blood. During the eight years (221-207 B.C.) that the Qin dynasty struggled for supremacy, the estimated population of China dropped from 20 million to 10 million. In the Three Kingdom period (222-589 A.D.) the population dropped from something like 50 million to about 7 million. After the Ming emperor Chang Hsien-chung conquered Szechwan province, he ordered scholars, merchants, officials, wives, and concubines murdered. He had their feet cut off and gathered into huge piles. In 1681, following the Triad Rebellion, an estimated 700,000 people were executed in one province alone. The great peace of the nineteenth century didn't touch China where, during the 15-year Teiping Rebellion, perhaps 600 cities were reportedly ruined, and as many as 40 million people were killed. Moslem rebellions in Yunnan province resulted in some 5 million deaths.

There were atrocities in Western Europe. Jews were blamed for the Black Death of 1347-1352, and thousands were slaughtered. The Spanish Inquisition killed between 100,000 and 200,000 people who were branded "heretics." Fanatical Protestants killed perhaps 100,000 women as "witches" during the Reformation. On August 24, 1572--St. Bartholomew's Day--the French King Charles IX or his officials ordered assaults on French Calvinists, and an estimated 35,000 were killed. During the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), perhaps 7.5 million people were killed. An estimated 137,000 people were murdered during the French Revolution and the ensuing civil war.

And, yes, there were horrors in the Americas. Aztecs killed people as part of their religious rituals, and Spanish conquistadors claimed to have counted 136,000 skulls outside Tenochtitlan. The Incas killed thousands for their religion, too. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, an estimated 1.5 million slaves died while they were being transported across the Atlantic. Between 10,000 and 25,000 North American Indians were killed as the United States expanded westward.

These are just some of the worst horrors. Before the twentieth century, I estimate that governments were responsible for at least 89 million deaths and possibly as many as 260 million. My best guess is around 133 million.

Again, these numbers don't count battle deaths. I estimate that before the twentieth century, those amounted to some 40 million.

I want to caution readers about the misleading precision of these numbers. They represent the totals [consolidation] of many estimates. I analyzed the estimates as best I could. Obviously, the farther back one goes in history, it's harder to verify numbers. Which is why I tried to establish a range and then indicate a magnitude which seems best supported by evidence. Although the numbers shouldn't be taken literally, I believe they do help identify the worst murderers and the circumstances.

I conclude that nobody can be trusted with unlimited power. The more power a regime has, the more likely people will be killed. This is a major reason for promoting freedom.

The Freeman: What were the biggest surprises to emerge from your research? Rummel: First of all, the unprecedented magnitude of mass murder. Nobody had tried to estimate it before. We have many books about demographics, like total population, the number of people who own telephones and cars. There's data on the number of people who die from heart attacks, strokes, cancer, and accidents. But until recently, there hasn't been any reliable information on the number of people killed by governments. Even though many of us were aware that governments were major killers, the numbers still come as a shock.

During the twentieth century, 14 regimes murdered over a million people [each], and it would be hard to find a scholar who could name half these regimes.

I was shocked to find that governments kill people to fill a quota. For instance, in the Soviet Union under Stalin and China under Mao, the government would set execution quotas. They would decree that perhaps 5 percent of the people are counterrevolutionaries, so kill 5 percent of the people. Writers, entrepreneurs, you name it--kill 5 percent. In retrospect, I can see that murder by quota was the natural thing for these regimes to do, because they had central planners direct production of iron, steel, wheat, pigs, and almost everything else by quota.

I was shocked to discover how officials at the highest levels of government planned mass murder. The killing they would delegate to humble cadres. So much for the notion of government benevolence. Powerful governments can be like gangs, stealing, raping, torturing, and killing on a whim.

Another shocking thing, for me as a political scientist, was to see how political scientists almost everywhere have promoted the expansion of government power. They have functioned as the clergy of oppression.

The Freeman: What was difficult about estimating the magnitude of government killing? Rummel: There's a vast literature, but it's widely scattered, it comes in many different forms, and it isn't indexed or otherwise organized. There are only a few scholarly books, such as Robert Conquest's work on Stalin's Great Terror, estimating the number of people murdered by government. It took me about eight years to go through all the relevant books, reports, articles, chapters, clippings, and the like and sort the information I found.

I then determined the lowest estimates and the highest estimates of democide, and arrived at what I call a "prudent" figure depending on various factors. I concluded that during the twentieth century governments killed at least 80 million people and possibly as many as 300 million, but the most likely number is about 170 million.

Even if it turned out that the low estimates were correct, it's more than twice as many people as have been killed in all the wars before the twentieth century.

From a moral standpoint, I doubt it matters much whether the number is 80 million or 170 million or 300 million. It's an unprecedented human and moral catastrophe.

The Freeman: Since authoritarian and totalitarian regimes suppress their records, how did you develop estimates for their murders? Rummel: Well, among the principal sources, there are usually those sympathetic to a regime and those hostile to it.

The low estimate for twentieth-century mass murders, 80 million, comes mainly from sources sympathetic to the regimes carrying out the murders!

In a few cases, regimes have publicized their murders, often to intimidate people. For instance, Communist Chinese government newspapers would report speeches by officials in which one might boast, "We killed 2 million bandits in the 10th region between November and January." The term "bandit" was standard lingo for presumed "counterrevolutionaries."

After Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1979, the Vietnamese justified the invasion by releasing data about Cambodian mass murders. They let Westerners see evidence of Khmer Rouge horrors.

Many people who escaped totalitarian regimes brought data about mass murders. They were unsympathetic sources, of course. For instance, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's volumes documenting the murderous Soviet gulag. I might add that he had an enormous impact undermining the moral claims of socialism. Many intellectuals, especially in Europe, remained socialists, but they turned against Soviet communism--and the Soviet Union, remember, was long touted as the place where socialism had achieved industrial power and social justice.

The Freeman: Tell us about your findings on peace. Rummel: First, long [well]-established democracies don't wage war on each other, and they rarely commit other kinds of violence against each other, either.

Second, the more democratic two countries are, the less likely they will go to war against [have intense violence with] each other.

Third, the more democratic a country is, the lower the level of violence when there's a conflict with another country.

Fourth, the more democratic a country, the less likely it will have domestic political violence.

Fifth, the bottom line: democratic freedom is a method of nonviolence.

The Freeman: What do you mean by "democratic"? Rummel: People have equal rights before the law. Fundamental civil liberties like freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, freedom of association. Free markets. Constitutional limitations on government power. Policies and leaders are determined through open, competitive elections where at least two-thirds of adult males have the franchise. Countries like the United States, Canada, Denmark, France, Great Britain, Sweden, and Switzerland.

The Freeman: Tell us about your evidence that freedom promotes peace. Rummel: I reviewed the evidence and historical studies going back to the classical Greeks.

For example, if one counts as a war any conflict in which 1,000 or more people were killed since 1816, the end of the Napoleonic wars, then there were . . . [no wars] between two democracies. There were 155 pairs [such as the Great Britain versus Germany, the U.S. versus Japan].involving a democracy versus a non-democracy and 198 pairings of two non-democracies [such as Japan versus China, Germany versus the U.S.S.R.].

The period between 1946 and 1986 involved the largest number of democracies--the toughest test for the link between democracy and peace. During this period, 45 countries qualified as democracies, and 109 as non-democracies. Consequently, these countries could be paired 6,876 ways, of which 990 were democracy-democracy combinations. Without going into detail, I applied the binomial theorem to show that the odds were 100 to 1 against the absence of war occurring by chance.

When you analyze other periods, qualify countries with various definitions of democracy, and estimate the impact of other factors such as geographic distance, economic development, military alliances, trade, and so on, democracy always comes out as the best explanation for the absence of war.

This is an incredible finding. It's like discovering a cure for cancer. We have a solution for war. It is to expand the sphere of liberty.

The Freeman: Why do you think liberal democracies tend to be peaceful? Rummel: Power is dispersed through many different families, churches, schools, universities, corporations, partnerships, business associations, scientific societies, unions, clubs, and myriad other associations. There's plenty of competition, and people have overlapping interests. The social order isn't controlled by anybody--it evolves spontaneously.

Democracy is a culture of political compromise, free exchange, peaceful negotiation, toleration of differences. Because time is needed for a democratic culture to develop and gain widespread acceptance, I stress that a peace dividend is achieved as a democracy becomes well-established.

Even though there might be a lot of government interference in daily life through minimum-wage laws, environmental laws, drug prohibition, government schools, and other policies, as long as a democratic culture remains strong, government officials must still negotiate with each other as well as with private interests.

By contrast, as Hayek explained in The Road to Serfdom--in his famous chapter "Why the worst get on top"--centralized government power attracts aggressive, domineering personalities. They are the most likely to gain power. And the more power they have, naturally the less subject they are to restraint. The greater the likelihood such a country will pursue aggressive policies. The highest risks of war occur when two dictators face each other. There's likely to be a struggle for supremacy.

Another important reason why democracies tend to be peaceful is that people have a say in whether their government goes to war. They don't want to die, they don't want to see their children become casualties, they don't want the higher taxes, regimentation, inflation, and everything else that comes with war.

When democracies do enter a war for reasons other than self-defense, politicians often find it necessary to deceive the public. In 1916, this was the case when Woodrow Wilson campaigned on a promise to keep the United States out of World War I, then maneuvered the country into it. And again in 1940, Franklin Roosevelt campaigned on a promise to keep out of World War II, then conducted foreign policy not as a neutral but as an ally of Great Britain and an enemy of Germany. My point is that in the United States, a liberal democracy, there was considerable popular opposition to entering foreign wars, and both presidents deceived the public, which wanted to remain at peace.

The Freeman: Some people suggest there are big exceptions to your claim that democracies don't make war against each other, like the War of 1812 and the American Civil War. Rummel: The War of 1812, of course, was between the United States and Great Britain, but the franchise in Great Britain was then severely limited. Parliament was dominated by members from "rotten boroughs," districts that aristocrats controlled. Booming regions like Manchester had little, if any, representation. Serious electoral reforms didn't begin to come until 1832, and major extensions of the franchise came decades later.

As for the Civil War, I don't consider the South a sovereign democracy. Only about 35 percent or 40 percent of the electorate--free males--had the franchise. President Jefferson Davis was appointed by representatives of the Confederate states, not elected. There was an election in 1861, but he didn't face any opposition....

There are other possible exceptions people sometimes mention, but none of them involve established democracies.

The Freeman: If democracies tend not to wage war against each other, they sometimes promote coups, assassinations, and other forms of violence abroad. Rummel: Such violence tends to be the work of covert agencies like the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, which have considerable discretionary power and aren't subject to detailed scrutiny by democratically elected representatives.

The Freeman: What about Western colonialism, which involved violence? Rummel: Democracies committed less violence than other types of governments.

For example, compare the way the United States and Britain treated their colonial subjects with what Imperial Germany did. In Africa, the Germans conducted a murderous campaign against the Hereros tribe, and some 65,000 people were murdered. Far worse was the Soviet Union which murdered millions of people in territories it conquered.

Democracies have given up their colonies with less violence than authoritarian or totalitarian regimes. Recall how the British gave independence to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. The most tragic fighting was between local rivals such as Moslems and Hindus. Hawaii, which the United States acquired by force, voted overwhelmingly to become a state, and Puerto Rico voted to remain a U.S. territory.

It's true some democracies did worse. France waged long wars in Indochina and Algeria. But the exceptional situation for democracies is the norm for authoritarian and totalitarian regimes like militarist Japan, fascist Italy, the Soviet Union, and Communist China.

The Freeman: Some people might say that although the United States is a liberal democracy, there's plenty of domestic violence. Rummel: It's true the United States has the highest murder rate among Western democracies, but there's decidedly more violence in other countries like Brazil, Burundi, Colombia, India, Peru, Rwanda, Sri Lanka, and Uganda. The United States is well below the world average in domestic violence.

More to the point, I'm talking about how to minimize political violence. While it certainly isn't the only source of violence, it's the worst. I say that securing liberty is the only reliable way of minimizing political violence--revolution, assassination, civil war, military coups, guerrilla war, violent antigovernment riots, and so on.

The Freeman: Did your research influence your personal views? Rummel: It helped convert me from socialist to libertarian.

If somebody had given a speech three decades ago, saying freedom is what promotes peace, and tyranny promotes violence, I would have said that was a simplistic explanation which couldn't possibly hold up. Much of my career, I had believed that complex social behavior requires many variables to explain and a complex theory. The surprise was that when I did the research, freedom came out as the single most important factor for peace and nonviolence. That freedom so preserves and secures life I now call the miracle of freedom.

The Freeman: What's your outlook for liberty and peace? Rummel: Our challenge is to extend the sphere of liberty which, in turn, will extend the sphere of peace.

There has been some heartening progress in recent decades. For instance, while there are many disputes in Western Europe, where democracy is securely established, they're routinely handled through diplomatic channels, the European Community, or other peaceful means. France and Germany even have been considering a common army. This would have been inconceivable to people during the 1930s.

Closer to home, there's the border between the United States and Canada. It's one of the world's longest borders, and it's unarmed. People in North America take it for granted, but it's quite an amazing phenomenon when you consider all the wars still being fought over territory. These examples involve liberal democracies, and peace is the norm.

Markets are strong influences for democracy. For instance, foreign direct investment, which now exceeds $1.5 trillion, transfers technology to host countries. It provides jobs. It trains local people in business. It helps nations develop their resources and human capital. Most important, foreign direct investment promotes economic development and a civil society independent of government, and this promotes democracy. America should cut its own trade barriers and encourage freer trade everywhere.

America should apply nonviolent pressure aimed at persuading nondemocratic elites to improve the human rights of their people and gradually move toward democracy. I envision a nonviolent crusade by the democracies, the most important one since the great crusade against slavery.

The Freeman: Thank you very much.

No comments:

Post a Comment